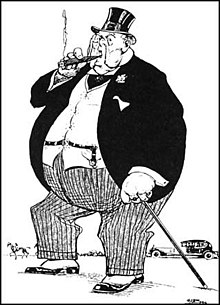

The FRC have picked up on mounting public anger regarding extortionate levels of Executive Director pay; enough is enough. For too long too much has gone to the top and too little to those lower down the pecking order. The average salary for the Chief Executive of a FUTSI 100 company is £5 million a year; and the inequality worsens every year. Discontent is so widespread that the Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) Select Committee and even our new Prime Minister are also calling for change.

The FRC have picked up on mounting public anger regarding extortionate levels of Executive Director pay; enough is enough. For too long too much has gone to the top and too little to those lower down the pecking order. The average salary for the Chief Executive of a FUTSI 100 company is £5 million a year; and the inequality worsens every year. Discontent is so widespread that the Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) Select Committee and even our new Prime Minister are also calling for change.

This isn’t a new problem. In 1995 Sir Richard Greenbury published his report which had been commissioned to look at what needed to be done to address excessive executive pay. Twenty one years later it is clear the report’s recommendation for changes to corporate governance have proved insufficient.

So yesterday the FRC announced it will be taking corrective action and in my opinion their intended actions are spot on. FRC stands for Financial Reporting Council. It is the national regulator responsible for setting UK corporate governance best practice.

They point out that directors on company boards are not paying regard to their responsibilities as set out by law in the Companies Act 2006. Sections 171 to 177 set out seven key responsibilities expected from a director. In particular uncontrolled executive pay (along with several other corporate woes which most recognise well but I shall not go in to here) is down to a disrespect of Section 172:

172. Duty to promote the success of the company

(1) A director of a company must act in the way he considers, in good faith, would be most likely to promote the success of the company for the benefit of its members as a whole, and in doing so have regard (amongst other matters) to—

(a) the likely consequences of any decision in the long term,

(b) the interests of the company’s employees,

(c) the need to foster the company’s business relationships with suppliers, customers and others,

(d) the impact of the company’s operations on the community and the environment,

(e) the desirability of the company maintaining a reputation for high standards of business conduct, and

(f) the need to act fairly as between members of the company.

This section of law clearly sets out that companies should avoid short termism, have regard for the interest of their employees, the community and the environment and seek to maintain a reputation for high standards. However spurred on by unpleasant socio-economic behaviours supported by thinkers such as Milton Freidman, many large corporates have quite happily ridden rough shod over these requirements. This has resulted in much of the corporate world becoming entirely self-centered and self-rewarding at the expense of society as a whole; a perverse race to the bottom of moral standards.

So the FRC’s message is welcome:

- Boards should pay more attention to their responsibilities under Section 172 of the Companies Act 2006 to both shareholders and wider stakeholders and should report on how they have discharged these.

- The Government should review the enforcement framework in order to establish an effective mechanism for holding directors and others in senior positions to account if they fail in their responsibilities.

The second point refers to the need to ensure Directors’ responsibilities are enforced since at the moment only the weakest of enforcement exists leading to fragrant disregard of the law.

I can’t emphasise how pleased I am to see this shift in national sentiment being reflected at the heart of where it matters. Businesses aren’t just about making profit at the cost of everything else. Like every individual and organisation they have a responsibility to above all serve society.

The indication that the FRC is having to resort to amending UK Corporate Governance to address the disregard for Section 172 (effectively beefing up the stick as opposed to carrot) raises the question why “the markets” haven’t addressed the shortfall in behaviour which is displeasing the public.

In my view strengthening the application of Section 172 of the Companies Act addresses the biggest downfall in our current capitalist model – and represents an attempt to drag capitalism out of the dark and back in to the light where it can truly serve society as it should. I hope the move will have the effect it intends!

Anchoring Strategy in Truth…

Strategies and policies signify decisions; usually made collectively by a group and developed over a period of time. They are made by people, based on their representations of the particular World situation. See my December 2012 post “Making sense of reality” which explains how representations form the fundamental psychological construct which enables individuals and communities as a whole to make sense of the World around them.

Faced with a decision an individual, or group of people, can either make it immediately using their existing World representations or they can postpone the decision to first actively seek to inform their existing representations. For low risk and routine decisions there may be no need to postpone, but when the stakes are high and the complexity great then taking more time to get it right is usually the best option.

Faced with a decision an individual, or group of people, can either make it immediately using their existing World representations or they can postpone the decision to first actively seek to inform their existing representations. For low risk and routine decisions there may be no need to postpone, but when the stakes are high and the complexity great then taking more time to get it right is usually the best option.

Strategy, policy and decisions are delivered by and through social means. The World situations within which they act are so complex as to often be difficult if not impossible to fully understand – let alone make an accurate representation of. In fact as my March 2015 article “Why a mutual?” indicated, hopes of uncovering an absolute truth might as well be parked. It is more a question of how much effort do you want to – do you need to – and are you able – to put in to getting closer to the truth?

And this is a really important question.

A corporate strategy seeks to align the functions of a business in relation to the outside world to achieve a vision and/or number of corporate goals. Sub-strategies and policies do similarly just with the internal and external boundaries differently defined.

The first step is for the corporate strategy to look within and in particular beyond the organisation by developing a representation of the World and situating the organisation (at least its representation of itself) within the World representation. This is the starting point from which the organisation and the World are to be manipulated to attain a future favourable situation for the organisation.

The first step is for the corporate strategy to look within and in particular beyond the organisation by developing a representation of the World and situating the organisation (at least its representation of itself) within the World representation. This is the starting point from which the organisation and the World are to be manipulated to attain a future favourable situation for the organisation.

The implication of getting the starting point wrong for the organisation is like blindfolding a person trying to navigate an obstacle course. Whereas investing time in developing an accurate representation gives a business its sight enabling it to safely navigate the World and quickly establish workarounds for new obstacles unexpectedly thrown in.

This is what led Dwight Eisenhower to say:

”Plans are worthless, but planning is everything.”

Eisenhower believed the knowledge of the environment gained during the planning process kept the planners “steeped in the character of the problem” which then allowed organisations to effectively understand and manipulate the reality around them.

In practice developing a representation of the World situation often involves using a mnemonics such as PESTLE, PEST or SWOT to help remind us of key broad elements of the World to consider. During the process, and with a number of other thinking tools available to apply, we actively look into the business’ external environment for evidence of relationships between things, trends, certainties, uncertainties, facts, fiction, risks etc. The more thoroughly we do this, the better the representation of the World situation will be.

In practice developing a representation of the World situation often involves using a mnemonics such as PESTLE, PEST or SWOT to help remind us of key broad elements of the World to consider. During the process, and with a number of other thinking tools available to apply, we actively look into the business’ external environment for evidence of relationships between things, trends, certainties, uncertainties, facts, fiction, risks etc. The more thoroughly we do this, the better the representation of the World situation will be.

A crude and inaccurate sketch map of the World based on a cursory glance will lead to ill-informed strategy, blind the business and likely cause failure. A comprehensively developed view of the world however, fully anchored in detailed evidence, will do the opposite.

I have too often seen the importance of this step completely undervalued. Notional, colloquial or half-hearted efforts to understand the situation are hastily packaged and then appended with a wish list from the dominant power within the business – often because the priority is simply to produce a document labelled strategy or policy for X or Y. This misses the point that it is the process leading up to the document that actually holds the value – the document merely evidences the process. The cost of this mis-prioritisation cannot be over exaggerated since as well as for understanding the organisation and World and engaging with both, the World representation is used for:

- understanding and managing risks,

- communicating, convincing and inspiring employees and stakeholders,

- building subsequent business cases,

- learning lessons by reviewing and amending it as knowledge grows and circumstances evolve,

- measuring and demonstrating progress,

- giving leaders the confidence they need to lead.

So what can we do to make the representation best serve these purposes?

- Bring to bear as much evidence as possible, prioritising what is considered the most relevant first,

- Use a scientific evidence based approach,

- Engage all stakeholders who carry their own sets of experience (evidence) which can then be pooled with that of the organisation (see also “Why a Mutual”),

- Minimise the psychological distance between the

observer (who is preparing the decision) and the object being observed (as my April 2012 essay “Can Communities Think” addresses). The added insight this enables ensures the strategy, policy or decision’s vision is a) based on a more accurate representation of the World and b) provides psychological pathways with minimal barriers for its stakeholders to engage with it.

Following this advice above might sound complicated – however there are well established strategy and policy development methodologies that can be flexibly applied to deliver these outcomes. Invariably they lead to a written strategy, policy, decision document. Leaders and decision makers should use these documents to ensure there is evidence of the methodology being followed with the necessary emphasis on developing the World and organisation representations. Ensuring a suitable and common methodology is widely understood by  senior employees within the organisation is fundamental for

senior employees within the organisation is fundamental for

organisational leaders. It should be sufficiently inculcated into the organisation’s way of doing business so that collective expectations revolve around applying it smoothly, properly and consistently.

Whilst these processes may seem onerous, it is difficult to overstate their value and importance.

I close this article with Albert Einstein’s famous quote “If I had an hour to solve a problem, I’d spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and 5 minutes thinking about solutions.”

Britain: A strong country…that works for everyone

Britain has chosen to Brexit, and “Brexit means Brexit”. Theresa May will trigger Article 50 by March 2017 and the two year countdown will begin for the UK to officially withdraw from the EU.

Britain has chosen to Brexit, and “Brexit means Brexit”. Theresa May will trigger Article 50 by March 2017 and the two year countdown will begin for the UK to officially withdraw from the EU.

The Prime Minister is clear that leaving the EU means for UK ending the right of EU people to come to reside and/or work in UK. Similarly the EU is clear that without participation in freedom of movement, there can be no access to the EU single market.

Liam Fox, David Davis and Boris Johnson are lined up to tackle this challenge head on. Any negative impact on trade with the EU resulting from withdrawal from the single market will be counteracted with a strategic repositioning of the UK on the global stage, namely a massive increase in free trade between the UK and the rest of the World. Liam Fox speaks of a renaissance of a two hundred year period in history where Britain led world trade – he refers to the 18th and 19 centuries.

However if the UK is to pin its hope on a strategy or a vision to bring about a new strong and global position in free trade, then this period of British imperialism and mercantilism partly if not largely brought about through piracy, bribery, jobbery, military force, colonisation and slavery (or profits from it) is not it.

A stronger position in global trade will be brought about by a strong, innovative, entrepreneurial people, nurtured and supported by a country with just government and institutions which work for everyone and champion meritocracy, opportunity and equity. That’s my vision and that’s the Prime Minister’s vision.

To Survive or not to Survive – What should we value?

Whilst I studied for my MSc in Philosophy of the Social Sciences, I was fortunate enough to lightly cover a broad spectrum of the seminal texts that form the foundation of the subject. My classes conveyed several of the key schools of thought and the variety of approaches they employed in a bid to make sense of the social world – naturalism, behaviourism, functionalism, hermeneutics, positivism , rationalism and more.

Whilst I studied for my MSc in Philosophy of the Social Sciences, I was fortunate enough to lightly cover a broad spectrum of the seminal texts that form the foundation of the subject. My classes conveyed several of the key schools of thought and the variety of approaches they employed in a bid to make sense of the social world – naturalism, behaviourism, functionalism, hermeneutics, positivism , rationalism and more.

Despite all these methods, one insecurity seemed to continue to plague the subject and indeed philosophy as a whole. Namely how to attach any kind of precise meaning to anything – Descartes was largely to thank for this after he doubted existence itself – only managing to defeat his scepticism by assigning his mind’s apparent ability to think, a singular certain existence. From this starting block, philosopher after philosopher tried to build up a larger collection of definite truths – items that could be assigned some kind of certain value – the Vienna Circle even sought to develop a means of uncovering more truth and value through maths-like operations which would start from a few certain truths and uncover many more.

Meanwhile I was also studying two units on Social Psychology. Social Psychology had its own similarly fundamental struggle – namely to understand what specifically motivates human behaviour. I learnt a number of theories, but here too no one theory seemed able to pin it down precisely. One system proposed that conscious humans were constantly trying to make sense of the world around them and defining it. Another claimed humanity’s evolutionary history now defined human behaviour. My conclusion was that for one reason or another consciously or unconsciously the human mind values one course of action over another and ultimately follows it. Behaviour is the result of some kind of process – the outcome of which is the one which is considered the most valuable at that moment in time.

Of course if humanity had never evolved consciousness and even sub-consciousness, then it would never of had the ability to make sense of the world, the ability of language or indeed the ability of any kind of behaviour at all. In fact if Darwin’s theory of evolution is to be taken seriously then everything or more precisely every characteristic of life lives because it has at one time or another in its genetic ancestry enabled survival. So why on earth then would not language, behaviour and in fact everything we do and say not be directly linked with a bid, past or present, for survival?

From this point onwards in my studies I found it difficult to take seriously any theory that did not put survival (either past or present) as the root cause for human behaviour – language included. And since human behaviour has led to social norms, institutions and culture, then survival in one form or another is behind these too. Everything that has value associated to it is now intricately associated with – defined by – past or present bids for survival.

Now of course just because one evolved characteristic has survived once does not mean it will survive again and so there is still good cause for society to consider how it thinks best survival will be achieved in the future – that is assuming one is still intent on survival. Does what we value today, because it once enabled survival, still merit the value we associate to it? Will it continue to deliver survival?

So if the above concepts are roughly right, for any project which seeks to influence society – understanding these concepts is important. Social science is still struggling to make sense of human behaviour – but if it is defined as I suggest by survival and will continue to be so, then understanding how this has happened might help to explain how it might continue to. At every point in the journey the question is – what should we value?

By looking at our existing society:

- at what is currently valued and what is not,

- at what value can be consciously ascribed too and what it cannot,

- at what value is unconsciously ascribed to and what it is not,

we can far better equip ourselves to help shape our behaviours, our communities and our lives so that survival and thus hopefully long-term well-being are secured.

Why a mutual?

Humanity has always been gripped by an urge to seek knowledge; “the truth”. Quite possibly because people believe having knowledge is most likely to help them live a happy and successful life e.g. find a good job, have enough food, find a partner, buy a home. However before you can look for knowledge, you first have to know what it looks like – what does it or does it not consist of? Fortunately for us Philosophers have for thousands of years, through the subject of Epistemology (literally meaning the study or knowledge or understanding) specialised in trying to establish the answer to this very question. For much of this time it was claimed that knowledge was Justified True Belief (the JTB model) i.e. something that was true, believed and could be justified. However this model has never fully satisfied critics, for the model always required other bits of knowledge in order to do the justifying with. Another epistemological model claims that there is no ultimate truth. The truth is what a community holds to be true. Today the community could believe the World is flat and for all intense purposes it is, and tomorrow it could believe the World is round. This would then constitute the new truth or knowledge. This form of epistemology is the foundation of the philosophy of pragmatism. The truth is what is believed by a community and allows it to survive.

Humanity has always been gripped by an urge to seek knowledge; “the truth”. Quite possibly because people believe having knowledge is most likely to help them live a happy and successful life e.g. find a good job, have enough food, find a partner, buy a home. However before you can look for knowledge, you first have to know what it looks like – what does it or does it not consist of? Fortunately for us Philosophers have for thousands of years, through the subject of Epistemology (literally meaning the study or knowledge or understanding) specialised in trying to establish the answer to this very question. For much of this time it was claimed that knowledge was Justified True Belief (the JTB model) i.e. something that was true, believed and could be justified. However this model has never fully satisfied critics, for the model always required other bits of knowledge in order to do the justifying with. Another epistemological model claims that there is no ultimate truth. The truth is what a community holds to be true. Today the community could believe the World is flat and for all intense purposes it is, and tomorrow it could believe the World is round. This would then constitute the new truth or knowledge. This form of epistemology is the foundation of the philosophy of pragmatism. The truth is what is believed by a community and allows it to survive.

So then what should a community believe. Well it could start by believing what it has seen with its own eyes. Surely if I throw a ball up in the air 100 times and it falls back to my hand, then if I do it once more the same will happen again? Well one would have thought so. However for hundreds of years philosophy has struggled with the problem of induction (or inductive reasoning). Inductive reasoning states that known facts can be used to predict the future e.g. because of gravity if I throw a ball up in the air, it will come back down again. However the problem of induction was a concern that there was no way of guaranteeing that something would not change, e.g. the laws of physics, or had not previously been observed; which meant on the 101st throwing of the ball in the air, it might just not come down. The basis of this concern is that in the vast World in which we live, what seems even a very simple situation is in fact infinitely complicated and so the next time we experience what appears to be an identical situation, it may actually unfold in a way previously unseen. Newton’s laws of gravity were held as an absolute truth for 2 centuries until new means of observation at sub-atomic level exposed anomalies with the laws; which prompted Einstein to discover the theory of relativity and supplant Newton’s laws.

So then what does this have to do with mutuality? Well a mutual organisation is a community consisting of members with certain shared values. Members are considered equal and have one vote each for deciding on key issues. This gives equal right to each member. It recognises each member’s set of personal experiences and beliefs which leads him or her to form an opinion before voting for a decision. This is important because by giving everyone’s personal experiences and beliefs equal validity a mutual takes into account every member’s experience of throwing a ball up into the air and the subsequent result. If one of those members had genuinely seen the ball not come down again, there would be reason to question whether or not belief in Newton’s or Einstein’s laws was sound and whether or not the mutual’s following of such principals was still likely to secure happy and successful future for its members.

By pooling together the views and experiences of the whole community, you are maximising your chances of someone seeing something which calls into question the validity of an existing theory and thus enables the community as a whole to investigate the theory in greater depth and if necessary remove and replace it. So this is the strength of a mutual. A mutual makes the determination of the truth (the determination of the right thing to do) everybody’s business.

A stir?

Does the internet not have the most amazing ability to embezzle those few precious hours of freedom following ones return home from work? Superfast broadband able to bring to one at the slight depression of a finger an unending assortment of jokes, quotes, messages, news, explanations, anecdotes – in fact these days one merely needs to utter the words “Okay Goog…” followed by whatever spurious request that strikes ones fancy and immediately and unquestioningly the digital world-wide brain of knowledge is plumbed and an answered picked out for us and neatly presented on the screen in front of our very eyes…… How could one not be ensnared?

Does the internet not have the most amazing ability to embezzle those few precious hours of freedom following ones return home from work? Superfast broadband able to bring to one at the slight depression of a finger an unending assortment of jokes, quotes, messages, news, explanations, anecdotes – in fact these days one merely needs to utter the words “Okay Goog…” followed by whatever spurious request that strikes ones fancy and immediately and unquestioningly the digital world-wide brain of knowledge is plumbed and an answered picked out for us and neatly presented on the screen in front of our very eyes…… How could one not be ensnared?

But time is slipping by and with it opportunity. Why not instead ink one’s quill and pen some words of received wisdom? Vent ones spleen after the day’s antagonisms? After all paper has no way to quell beliefs and aspirations. But of course is there the need for any more than oneself for this to indeed happen? Where to start? Where to end? How not to doubt oneself?

Luckily for me however a good friend of mine reminded me that the parchment of a blog is little more than the opening statement of a conversation. No more… no less…. How many times has one in anticipation made the opening statement to a conversation only to find no response is forthcoming. Ones words had no more effect than the exhalation of ones breath and yet no harm is done.

And so today pen has touched paper, digits depressed keys and what is there of it? Well if there is no more than nothing then no harm and otherwise perhaps the unexpected. For me, no more than that is reason enough.

When Capitalism goes bad!

Just keep turning the handle!!!

A short quote from Wikipedia page on “Production for use” that I would like to share:

A number of irrational outcomes occur from capitalism and the need to accumulate capital when capitalist economies reach a point in development whereby investment accumulates at a greater rate than growth of profitable investment opportunities. Advertisement and planned obsolescence are strategies used by businesses to generate demand for the perpetual consumption required for capitalism to sustain itself so that instead of satisfying social and individual needs, capitalism first and foremost serves the artificial need for the perpetual accumulation of capital.

Surely this is immoral? Hence should it not be made illegal. The problem comes from the difficulty in proving whether something is or is not to the benefit of the consumer. For sure it should not be assumed that the consumer knows.

A couple of other associated and interesting Wikipedia articles I’d like to highlight:

More to follow….

The Debate on Marriage

Recently on my various personal social media accounts, as well as reported in the media, there have been a number of reactions to those who oppose or question the merits of gay marriage. The type of responses I am referring to are vociferous condemnations which leave little room for discussion. For the respondents there are no questions to be asked or answered on the matter – the limiting of traditional marriage to a man and a woman is wrong – full stop!

Recently on my various personal social media accounts, as well as reported in the media, there have been a number of reactions to those who oppose or question the merits of gay marriage. The type of responses I am referring to are vociferous condemnations which leave little room for discussion. For the respondents there are no questions to be asked or answered on the matter – the limiting of traditional marriage to a man and a woman is wrong – full stop!

Off the top of my head I have 3 reasons for which this makes me feel uncomfortable:

Firstly the manner in which no room is left for discussion constitutes nothing less than an authoritarian claim to absolute truth; a stance positioned to force other views on the matter, wherever they may be on the spectrum of agreement or disagreement, out of the public sphere.

Secondly I question what argument they have for taking such a stance bearing it is generally recognised by social scientists that there is no such thing as an accurate prediction of what is right and wrong when it comes to social matters.

Thirdly their stance apparently lacking in substantial argument, makes little reference to the roots of culture.

It is the third point which concerns me most. How will a change in cultural practices affect society? It cannot be predicted as there are too many possible un-intending effects to consider. In keeping with the Darwin’s concept of evolution one can say that the net effect of specific practices that have survived millennia must have emerged as effective or fitness enhancing, despite any negative side-effects and a pragmatist would claim that what is right is what stands the test of time. On the other hand what stands the test of time may not stand a recent change in our environment.

So have there been any changes in our environment which would mean the traditional concept of marriage is no longer valid? What constitutes a change in environment? The questions stretch out ad infinitum….but this I feel is an important and so far under-explored area of the debate.

Perceptions, Concepts and Representations – Making Sense of Reality

The human brain is arguably the most complex thing known to humankind and recent times have seen it become the subject of intense research around the world. Despite now regular revelations regarding the nature of the brain, it still remains shrouded in mystery. Social Representation Theory (SRT) is a paradigm within Social Psychology conceived by Serge Moscovici in his book Psychoanalysis; it’s theory and it’s public. SRT does not claim to explain the complexity of the brain and all human thought but does offer an explanation of how we make sense of the world which for humankind is inherently social, and how we orient ourselves within it.

In this article I highlight one of the key elements of Moscovici’s theory. An element which, if true and intuitively to me it seems so, has enormous implications for our understanding of how we make sense of the world. This element is the process of representation.

Before referring to Moscovici’s words let me clarify the difference between two terms that he uses; perception and concept. Perception is the psychological sensation an individual experiences when subjected to a sensory stimulus. For example the sight of a landscape or sound of a tune; perhaps even a combination of more than one sense e.g. sound and sight or sight and smell. A concept however is the trace that is left behind in a person’s mind once the perception is over i.e. the sensory stimulus ceases leaving behind what we colloquially call a memory. A concept when called upon in many ways seems able to recreate the original sensory experience. The recreation however is not an exact copy. For example if you think of someone you have recently met for the first time, you may well recognise him if you saw him or her a second time. However you may not be able to recall from memory the colour of the person’s eyes. Furthermore the concept may have emphasised, biased or even distorted elements of the original sensory experience.

Returning to Moscovici’s words; how does he describe the process of representation? He says it is a “process that makes concepts and perceptions in some sense interchangeable because they generate one another” (Moscovici 2008: 15). This is a fundamental claim. To the layman it may seem a bizarre exclamation. For one easily understands how a perception gives rise to a concept – e.g. after seeing something one has the ability to recall it because the visual experience creates a memory. But how does a concept generate a perception? How is what we perceive shaped by past memories? Spared a little thought however this actually does not seem quite so surprising. For example a friend walks up to you, welcomes you and asks you how you are. Now without past memories, the perception would be the sight of a person in front of you and the sound of a series of noises emanating from his mouth. Taken to the extreme however, the pure sensory stimulus would be the sight of strange moving shapes and colours and then a series of noises coming from somewhere. Now of course this is not at all how we would perceive such an event. On the friend coming up to one, one immediately recognises the concept of a person. Then one recognises the features of the person and that the person with those features is the friend concept. Emanating from the moving opening located towards the top of his body, the mouth concept where one expects to hear sounds by which people can communicate, one hears a series of noises. The noises are instantly recognisable as words and are structured in such a fashion that one can decode a message. The message is what one would expect from meeting a friend and as it finishes in a question, a response is required. This is a simplistic example, but it starts to show the enormous part that concept has to play in shaping perception. The representation process uses concepts “to organise, relate and filter” sensory stimuli giving us perceptions that are structured and meaningful. Furthermore these perceptions transform existing concepts and generate new ones; changes that will themselves cause the shaping of future perceptions.

The above example uses the concept of a friend. A friend by definition is something that we are familiar with. It draws on matured concepts of the friend. But how do concepts shape things that are encountering for the first time? Moscovici claims each mind has its own logic for doing this. The logic is used to first anchor then objectify a new experience. It does this by using existing concepts as symbols and analogies to ground the unfamiliar in the familiar – e.g. on first sighting a car, one might draw the analogy that it is a self-powered cart, or symbolise it as an object for moving things. The logic which undertakes this is itself created from foundational perceptions and concepts. These foundational concepts are often rooted in myth, religion and science. Not only does this logic remain an unfinished product which continues to evolve as new concepts and perceptions are acquired but it remains unstated, unwritten and under normal circumstances not something that we control consciously.

Now let us consider further representation; the process of concept and perception generating one another. We have said that concepts or memories shape what we actually perceive. Now the collection of concepts that each individual holds must be different for everyone; no two individuals have had exactly the same experiential history (ordered set of experiences). Hence the shaping effect of concepts on perception is different for each person and so perception can only ever be a personal experience. This could be considered stating the obvious i.e. everyone has his or her own point of view. However conversely we find it difficult at times to understand how another person perceives exactly the same event so differently to oneself. We now have a suggested process which explains how this might come about. Referring to either concept or perception by itself now ceases to be very useful as they always act together and so representation can be used to refer to the output of the representation process.

Two questions arise from this: How much do representations differ or correspond from person to person? What are the circumstances that lead to this degree of difference or similarity? We can shed light onto a possible answer for the above questions by considering the answer to a further question: What are individuals doing when they engage in communication? Simply put each individual is sharing their personal representations. For the communication to succeed there must be a minimum degree of compatibility between representations. Otherwise the messages would simply be lost in translation. Furthermore each sharing act further shapes the existing representations of the communicating individuals. This has a kind of normalising effect and the outcome is a body of normalised but not identical representations which are easily recognisable between individuals. This body constitutes a shared reality or a social representation to which individuals can socially relate. Those sharing this shared reality are then part of a community. Depending on the community, the shared body of representations can be large or small. The nature of the similarity will depend on what is generally shared between individuals and how it is shared; not only in terms of communication, but also shared practices. For more information on this process see Knowledge in Context (Jovchelovitch 2007: Chap 3).

It is interesting to pry a little deeper into the normalising process for it is the process which will define the shared reality. How does it take place? Whose representations become the dominant shared ones? Whose reality is the “true” reality?

Having started from the psychological process of representation we find ourselves now dealing with the community practices and communication. It is those practices and communication that significantly contribute to the creation of the representations in our minds. An authoritarian social world where there is a strong hierarchy and top down power relations generally leads to less variety in representations. Practices, communication and experiences are mostly controlled by the lead authority. Approved representations are pushed down rather than allowed to generate freely by flowing back and forth between individuals. Conversely a social world with a variety of competing authorities and a flatter power dynamic allows a wider range of perceptions and concepts to flourish; no one individual source of representation is dominant. The above is only a brief example of how social dynamics and in particular the characteristics of communication can affect the normalising process and determine which representation becomes dominant.

If one is in a position to influence the normalising process, to determine which representation will be the dominant one, the one that will define reality within a society, how does one first nail down the truth? Representation is after all an individually specific experience. So who is the holder of the correct one which should form the basis of the shared or social representation? The notion of correct one itself is an interesting matter. If we take it to mean the representation which brings most well-being to society the problem rapidly gravitates towards challenges that have plagued philosophy and social sciences for centuries and continues to do so; that is how does one establish what will bring about the greatest social well-being? Even the meaning of well-being is up for grabs! Despite all this doubt and uncertainty perhaps as a minimum the following can be said: Each individual has a personal representation of a shared event; personal because it is shaped by the individual’s personal experiential history. The difference in experiential history means every individual perceives something which another individual will not. So each representation has the potential to inform another representation. Making the assumption that a decision is best made with the greatest amount of information relevant to the decision available then it would seem wise to gather and examine as many different representations of shared events as possible. Each representation will have its own contribution to make.

To say anything more than this regarding making good decisions and determining what is and is not true would be unwise. However we have already made a significant claim for to gather all possible representations on a shared experience requires a positive effort and a special set of social circumstances. This does not mean minority representations must be captured and used as the dominant shared social representation. Rather all representations must be located and captured. This requires a social dynamic where minority representations are not instantly distorted by dominant representations. Creating the social environment which gets this far would seem an achievement in itself; one which leaves communities best placed to make informed decisions that take into account reality as it is for all community members.

Jovchelovitch, S. (2007). Knowledge in Context: Representations, community and culture. London: Routledge.

Moscovici, S. (2008). Psychoanalysis: Its image and its public. tr. David Macey (orig. 1961). Cambridge: Polity Press.

What counts as utility!

I’ve been meaning to write a post for a good while now and at last I have been motivated to get on and write. What possibly could have done this? No other than the shortfalls of modern economics…

I’ve been meaning to write a post for a good while now and at last I have been motivated to get on and write. What possibly could have done this? No other than the shortfalls of modern economics…

I must start by saying that I am not an economist and this post should be taken as a layman’s understanding informed by world news and a sketchy philosophical and psychological perspective gained during my year of study at LSE. I will question the lack of economic models to give value to psychological well-being. Although not an easy task to accomplish the total lack of psychological outcomes being incorporated into utility models has led to national cultures becoming materialistic at the cost of social values.

Whilst probing into the matter of happiness as part of my dissertation writing I was yet again confounded by the narrowness of interpretation that economists afford to the concept of outcomes. Economists are interested in outcomes because their practices revolve around the theory of utilitarianism and utility. Below are definitions from two of the theory’s key traditional advocates. Jeremy Bentham wrote (circa turn of 18th century):

“By the principle of utility is meant that principle which approves or disapproves of every action whatsoever; according to the tendency which it appears to have to augment or diminish the happiness of the party whose interest is in question: or, what is the same thing in other words, to promote or to oppose that happiness. I say of every action whatsoever; and therefore not only of every action of a private individual, but of every measure of government.”

It is clear enough here that, for Bentham, the only outcome that is of relevance is happiness. John Stuart Mill a follower of Bentham in his seminal book Utilitarianism(1861) defines the Greatest Happiness Principal as the principle which:

“…holds that actions are right in proportion as they tend to promote happiness, wrong as they tend to produce the reverse of happiness. By happiness is intended pleasure, and the absence of pain; by unhappiness, pain, and the privation of pleasure.”

Again Mill leaves little room for interpretation; actions that induce pleasure are to be promoted and pain, avoided. The utilitarian principle then claims that decisions should be made in order to maximise utility or happiness. This implies calculating what utility will result from an action and then approving of it if it maximises utility. However these moral models which have formed the foundation of modern economics have been plagued by a major problem. That is how exactly to establish what brings happiness?

It is here over the years that narrow interpretations and assumption have been made by numerous specific agents and groups in order to serve various ends. The happiness theories or models have been packaged under various banners such as cardinal utility, ordinal utility, revealed preference theory, expected utility and more. Each of these is a method of determining quantitatively or by ranking the utility to be gained from a certain choice. The choosing agents are assumed to be self-interested all-knowing rational agents (an assumption which in itself opens a can of worms that we shall not deal with here). Revealed preference theory was that proposed by the behaviourists. This school of thought chose explicitly to ignore the mental aspects involved in making choices to promote happiness, instead establishing utility on how people showed in practice what their preferences were. What they preferred most could then be considered as that which had greatest utility or providing most happiness.

What the behaviourist model did explicitly however the others did implicitly i.e. failed to take account for psychological outcomes. They failed to take account of the fact that every action taken by an agent has as an outcome a change in the psychological state of the agent, certainly unconsciously if not consciously i.e. new memories, understandings, beliefs or habits which are physically constituted by small changes is neural states within the brain. Those 2nd and 3rd parties influenced in some way by these actions also undergo a psychological change. Ascribing utility to the changes in psychological states is difficult and still only partially understood which may explain why any effort to account for these outcomes is omitted from utility models. Although this significantly simplifies the utility accounting process it leaves physical non-mental matters as the sole objects of utility. This amounts to a significant oversight as I shall now explain.

As we go about our everyday lives we are continually concerned with surviving and self-fulfillment. This is most obvious when we eat, drink, breath and seek shelter. Absence of any of these for sufficiently long will soon leave us very sick and ultimately dead. In our daily business of acquiring these requirements and others needs, which now involves highly complex social mechanisms, we only too often overlook one of the key things which society needs to function. That is people who are socialised and as a minimum seek to provide for their own well-being. In many cases, particularly through the system of division of labour which is employed in almost all societies, individuals are also required to contribute to the well-being of others. This system of “if you scratch my back I’ll scratch yours” leads (or is supposed to lead) to a net result of societal well-being. So well-being is ultimately created (at least harnessed) by people for people. People are the common ingredient. A person who does not create well-being or even destroys well-being will reduce the net well-being on earth and deprive society of its benefits.

Now the psychological state of a person is partially complete at birth, however for the rest of an individual’s life, experiences will as already mentioned cause psychological changes to the individual in the form of beliefs, memories, skills, habits etc which all have their specific neural state in the brain. So in a sense the person continues to be created throughout their life. These developments have the potential to increase or decrease the extent to which an individual creates well-being. This whole concept is particularly complicated because we may not be aware of some of these changes i.e. they are subconscious. As a hypothetical example if as a child one is severely beaten as a form of punishment, it would seem likely that later in life as a parent one would be more prone to use the same method when disciplining one’s own children; even for psychologically simple reasons such as beating is the only way one had seen discipline in action or because it is a behavioural pattern which heavily imprinted itself on one’s mind and therefore is more likely to display itself in the future. So when calculating the utility of beating one’s child in order to discipline them, as an outcome one should not only be considered the immediate disciplinary outcome, but also the possible outcome of creating a person who also will beat his future children for the same reasons. Of course, this is only one possibility; it could also lead to the individual beating others in non-disciplinary events because it is perceived as acceptable behaviour. Or it might result in someone who is psychologically scarred by receiving beatings and thus develops chronic depression as an adult and needs to live on benefits for the entirety of his working life! And of course these effects could well roll on through the generations amplifying the effects significantly.

So it is these people making effects, and as I say every action has them to a greater of lesser extent, which are not considered in utility calculations despite their importance. Every action taken always has a psychological outcome which can either increase or reduce overall happiness and thus according to the classic utilitarianism should be included in the calculations of utility.

In mitigation to economists, I admit that calculating these outcomes is very difficult as they are very hard to detect, measure and then assign utility to. Furthermore I must admit that it is not simply economists who are guilty. In moral philosophy utilitarianism makes the same assumptions and omissions. This omission has meant perverse moral judgements. For example utilitarianism it could be argued supports the harvesting of organs from one healthy individual leaving the person dead in order to save the lives of 5 sick dying individuals. Whilst this on the surface has an outcome of 5 saved lives at the cost of 1 (which is better than having 5 dead), it does not take into account the psychological implication that such actions have on society i.e. that it is alright to go around killing an innocent person to save another. Apart from anything else everyone would live in fear of having their organs taken from them; resulting in widespread unhappiness!

However throughout economics there has been a thorough disregard for psychological outcomes in utility calculations. Usually money or the monetary value of items is taken as the sole and direct measure of happiness. Yet these items which are assigned values rarely if ever represent human psychological qualities. This therefore seems to be a model which denies the value of human qualities.

I have recently stumbled upon another flavour of utilitarianism which has yet to earn an entry on Wikipedia. It is called procedural utility (see here for explanatory paper). This type of utility recognises that it is not always simply the outcomes that matter, but the procedure that brought about the outcome that is also very much important in determining the amount of utility to be gained from a certain action. For example in a court hearing, it is not only the outcome of the hearing that matters, but also whether those affected felt the hearing was procedurally fair. Another example might be that in a functioning democracy, utility is not only gained from getting the representative one voted for into power, but also simply from being able to vote and take part in a self-determining process. In the commercial world, it could be simply how a client is treated by the vendor in a sales procedure. Now whilst procedural utility argues, in my opinion correctly, that all these types of procedures that produce utility should be included in economic calculations of utility, my concern is why in the 21st century such considerations are still merely considerations and not fact. In the case of the court hearing, clearly procedural fairness is vitally important as the product of such courts is supposed to be just that, not a material value that is represented monetarily or in some other materialistic fashion. In the case of the sales situation, a salesman is by definition supposed to provide a service to the customer. If he mistreats the customer then surely this is a disservice.

For too long economists have disregarded reality and where real value lies. By inventing models which attach no value to psychological well-being or tendency to produce well-being they have significantly contributed to a society which values money and material, but not mental well-being. Meanwhile politicians have pandered to the financial money markets and economic structures which are entirely based on these economic models and unsurprisingly over the years national cultures have been significantly affected, now giving more value to money and material items that to people themselves.